|

The result of the Jess Varnish employment tribunal appeal prompted me to reflect on an interview I had with British Cycling more than 10 years ago. It was for Program Manager for the 2012 Olympics. I did not get the job and although I was disappointed at the time, it now feels like I may have dodged a high performance bullet.

One memorable question I was asked was ‘what do you think business can bring to sport?’ Coming from a project management type background my answer consisted in part with the standard ‘on budget, on time, to quality’ mantra along with some with process improvement, Six Sigma lean process stuff. I probably even meant it at the time. Asked the same question now I would answer it differently. Over the last 20 years or so, the application of business ethos to sport has seen it devalued to a numbers game without bringing anything that could be seen as ethical best practice and accountability. Seemingly passionless, much elite sport performance looks like a rather dry box ticking exercise characterised by ‘delivering the plan’. The injection of huge sums of money by either commercial sponsors or lottery funding has not led to sport learning anything from business, it has just become a business. And, if you judge it by results alone, a successful one at that. More medals, more champions, more success, more world records. For National Governing Bodies, your elite runners, players or riders must win at the Olympics or World Championships or funding is withdrawn and the senior management team lose their lucrative salaries. Ostensibly the sport in question will lose its funding too but as little makes its way to the grass roots, how much that matters is questionable. The fall out in terms of collateral damage to those without a key to the executive bathroom – the administrators, coaches, athletes and even volunteers is significant. Unfortunately, some international and national governing bodies, or more accurately some of the people who occupy positions of influence in them, seem largely unburdened by rules of ethics, professional standards or law that governs behaviour in business. Put large sums of money in to an organisation without adequate accountability but with a clear goal to win - or else - and it is a short step to win at any cost and all that entails. It’s not just the questionable stuff that organisers of sport at national or international level are involved in – the bungs, ‘gifts’, accusations of abuse, bullying and dubious substances – it’s what is considered to be above board that indicates how dysfunctional these organisation are and raises serious questions about how suitable some people are for the influential roles they hold. For example, in what world is it acceptable to fly members of staff overseas to pick up performance enhancing drugs for a doctor (yes a doctor, a qualified medic employed by the governing body) to inject a runner in a hotel room a day before the London Marathon? If this is considered unremarkable, keeping a few testosterone patches in a cupboard is not much of a stretch. Other than the embarrassing enrichment of an elite cadre of plausible sounding chancers, the more sinister impact of this ‘businessification’ of sport is the creation a legacy of mentally and physically damaged participants. Sold a dream of a career in sport they become nothing more than a unit of resource that complies with program requirements and hits the KPIs or gets unceremoniously dumped. Or prematurely injured. Or offered inhalers when they do not have asthma. Or burned out in their 20s. Or bullied and abused to the point of mental and physical exhaustion. You can see this unravelling in the media now with gymnastics. It is beginning to look like elite sporting performance can only be delivered with a level of inhumane coercion and control. Surely, this cannot be what sport, at any level, is about? Fundamentally, sport is an escape from the humdrum of process, interminable meetings and eating the corporate sandwich. it should be fun, exciting, unpredictable and contain moments of joyous surprise. It is a lot more than just another day at the office. Asked the same question again, I would say sport at an organisation level needs to adopt the accountability, transparency and ethical codes the best businesses aspire to because it must not be allowed to facilitate a structure that licences abuse of any kind. If that comes at the sacrifice of success judged by medals, so be it.

1 Comment

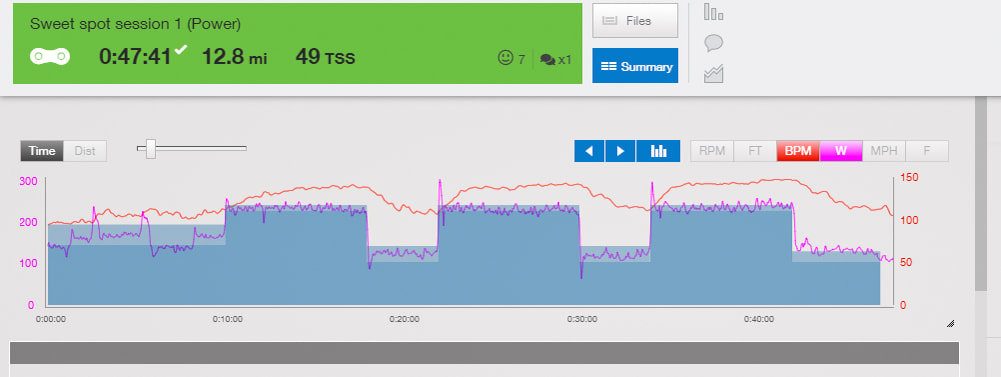

A recent comment from a rider got me thinking. I was reviewing the data from one of her sweetspot sessions and I wrote ‘all in parameters, good shaped HR curve’ in the Post Activity Review box helpfully provided by Training Peaks . ‘Great!’ she said, ‘What does that mean…?’ Fair comment, I’d slipped in to using unhelpful jargon and worse still. I’d slipped in to writing notes in training records as 'feedback' that were more use to me than her. Bad coach, bbbbaaadddd coach. Lesson learned, but it did remind me to check my use of language and force me to explain what the jargon meant to my bemused rider. It also prompted me to reflect on just how much effective use of data has become vital in my coaching practice. If you’re in the cycling matrix – by which I mean using GPS enabled data recording including power and heart rate measurement - and you regularly upload it to an App (Strava, Garmin Connect, Training Peaks) you’ll be familiar with the colourful blocks, graphs, maps and pictures produced. Whether you bother looking at them or not is another matter, but the the App will collate your data and try to turn it in to digestible performance information. Some of it is useful, some of it less so. For me as a coach, the most powerful performance metrics are power, heart rate (HR) and time. For our purposes HR can be defined as an input measure (an indicator of how hard you’re trying), power as an output (the product of your efforts) and time is that thing Einstein talked about although we can define it here as three 8 minute efforts with 4 minutes rest in between. Phew. In the diagram above, the boxes describe the session, the blue line is power and the red line is HR. Every rider is different but here you can see power remains fairly constant for the efforts and HR arcs upwards gently, but progressively more so, for each block. This indicates increasing effort is required to maintain consistent power. A good session completed within the prescribed parameters. Sweetspot efforts tend to be in multiples of 8, 10, 12 or 20 mins at 88 – 93% of FTP with varying rest in between dependent upon what effect you’re trying to create. They mimic volume riding without all that pesky getting dressed up and going outside for hours on end. Very generally, longer sweetspots tend to work best at the end of a block of training maybe just before an FTP test, shorter less stressful ones are better soon after an FTP increase to see if the power/HR correlation makes sense. Over a period, the delta between the HR and power curve alters as fitness changes. This is true of all sessions but sweetspots are useful because of the relatively long length or the effort giving time for HR to respond and stabilise. Increases in fitness are often indicated by the HR curve flattening with power remaining constant, or power increases over zone (or both if you’ve left it too long to boost the FTP settings). Steeper HR increases or drops below the power zone indicate the session is maybe too hard if that’s not what was intended. This can indicate an adjustment to the sequence or intensity/duration of training sessions is needed to ensure fitness matches the planned goals. Over a period of a few weeks, a data trend for a rider develops meaning better targeting and sequencing of sessions during any week to reflect the stress of a previous week and allow for appropriate recovery or aim to peak for a forthcoming event. The evaluation of data at this level allows fine adjustments to sessions to ensure progress is being made without constant FTP testing which is psychologically and physiologically stressful and can be a rather blunt and overused tool. So what does this mean for you as a rider? Your data is powerful stuff, it is ammunition to make you progressively stronger and faster so...

Used effectively, training data will help protect you from injury and over training and give you empirical evidence your fitness is improving or, if it isn’t, what needs to be changed to bring it on track. Fundamentally, accurate interpretation of your data means productive use of your time to achieve maximum training benefit and bigger improvements in fitness than you could hope to get without it. With the rise of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence, could you let the matrix do this for you – avoiding inconvenience of finding, and paying, a coach?. Algorithms are learning fast but they don't cut it, yet, although as AI becomes more sophisticated and we upload more human biometric data, it is likely it will become better at interpreting human behaviour and responses over time. I guess how scary this is depends on whether you think of Brave New World as a good idea or not. However, the machines aren't there yet and, as much as it irked me at the time, I was gratified to see my Garmin 520 once telling me I needed 42 hours rest in the middle of a 10 mile TT. Even if the advice was good, I’d seriously question the machines message management technique. Rich Smith likes machines and is a fan of the first two Terminator films. He thinks the others were, frankly, rubbish. He has coached the GB Transplant Cycling team for 10 years, is a British Cycling qualified Level 3 coach and a mature psychology student. He spent 30 years responding badly to people in authority in senior roles for Barclays, HSBC, British Waterways and National Grid Property and will probably help the robots out when the time comes.

|

AuthorThe ramblings of a cycling coach... Archives

May 2024

Categories |

|

© COPYRIGHT 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed